Shinjuku Station, it’s half past five in the morning and it’s dawn in Tokyo. Millions of people walk steadily without bumping into anyone with a single goal: to get into the corresponding train car so as not to be late for the office.

One of the main protagonists of this daily picture are the Japanese salaryman, executives (a masculine term only, since in Japan women are called Office Ladies) of a company, generally considered low-ranking.

In the 1980s, the salaryman’s life was a good aspiration for the country’s young people, as in other parts of the world it could be to become a civil servant: a stable job after finishing university, usually for life, in exchange for a dedication without limits to the company and a good relationship with your professional contacts for leisure moments.

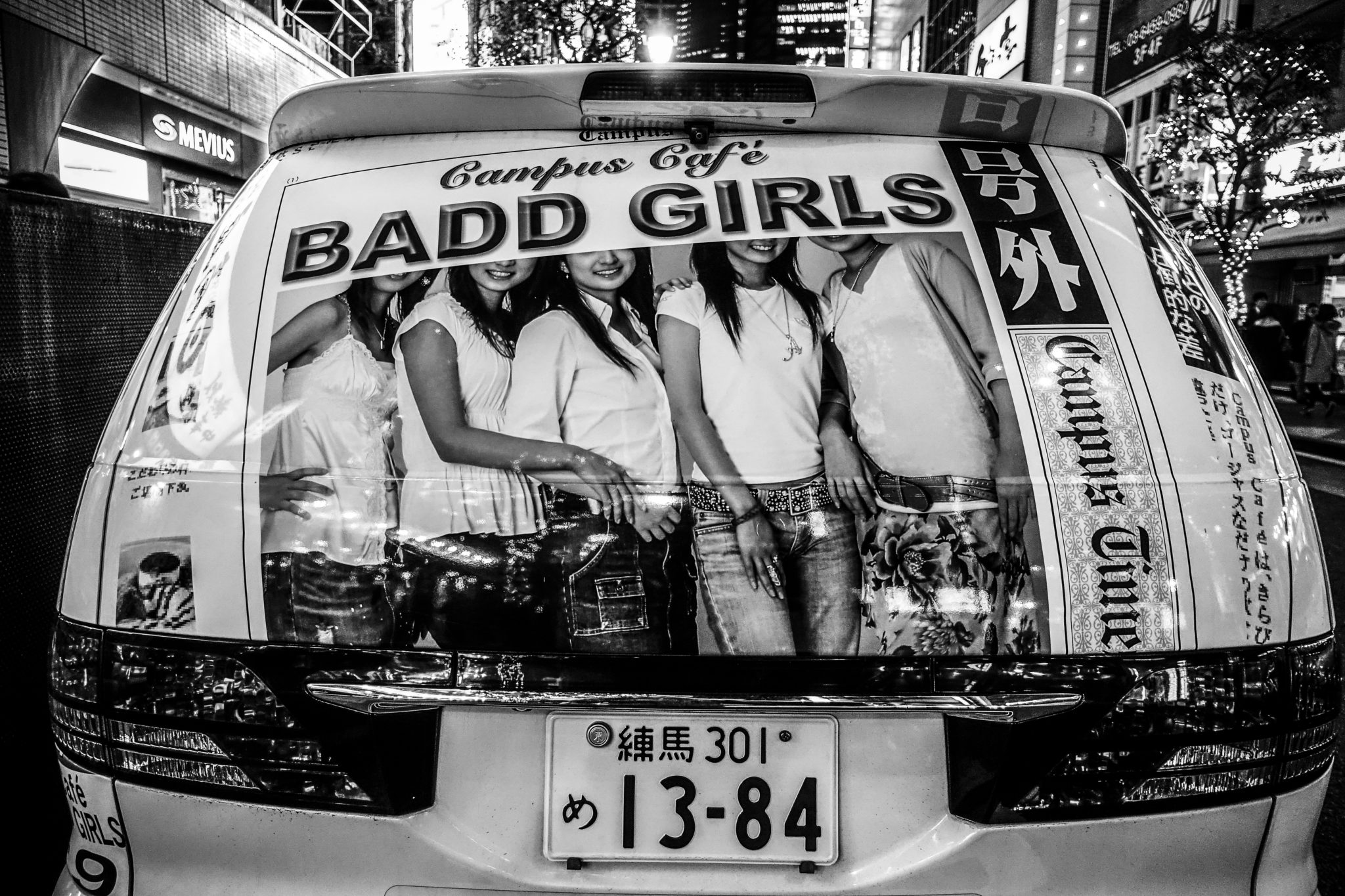

However, everything changed as a result of the bursting of the real estate and financial bubble in the early 1990s. The crisis brought consequences such as the wage freeze or the end of stable and lasting employment. Japanese society began to get used to dealing with new terms such as work pressure, stress, worries or nervous breakdowns from overwork. To all this, there were frequent problems such as alcoholism, exhaustion, or the lonely life of these workers who spent their days between work, izakayas (typical Japanese taverns) or some hidden brothel in the city. A situation that in some cases ended up leading to what is known as karoshi, the death of employees due to overwork. In 2015, for example, more than 900 cases of karoshi were recorded in Japan.

In recent years, due to the increase in Karoshi cases, this “overwork” has become a global problem in Japan. Today, the Japanese working class continues to fight for their rights and the government is in the midst of reviewing current labor laws. Greater time flexibility, aid for families in need of work travel or the control of overtime at work are some of the measures that are being taken to end this social scourge.

Changes in the Japanese labor system happen very slowly and as long as these measures do not begin to take effect, the salaryman will continue to get up at five in the morning, he will continue working an average of eleven hours a day, with his overtime included and when his shift is over He will attend the izakaya with his colleagues in search of alcohol and leisure. After all this and only if he has a free space, he will come home and will be able to see his wife and his children for the first time.